Everyday life in the hip-hop generation differed in Los Angeles compared to New York City, as one would expect. When it came to partying, DJ crews (Uncle Jamm’s Army, World Class Wreckin’ Cru, the latter featuring a very young Dr. Dre and DJ Yella) ran the city playing setlists full of electro-funk and techno. Their dress code leaned toward the sequins and leather of Prince and P-Funk. White supremacy drove police brutality on both coasts, but the LAPD conducted itself like a gang on the order of the Bloods and Crips who populated California. Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash didn’t mean as much to L.A. youth as funk bands like Zapp.

Everyday life in the hip-hop generation differed in Los Angeles compared to New York City, as one would expect. When it came to partying, DJ crews (Uncle Jamm’s Army, World Class Wreckin’ Cru, the latter featuring a very young Dr. Dre and DJ Yella) ran the city playing setlists full of electro-funk and techno. Their dress code leaned toward the sequins and leather of Prince and P-Funk. White supremacy drove police brutality on both coasts, but the LAPD conducted itself like a gang on the order of the Bloods and Crips who populated California. Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash didn’t mean as much to L.A. youth as funk bands like Zapp.

Tracy Marrow, aka Ice-T, had been a soldier and a jewel thief by the time he decided to put his rhymes on wax. As an affiliate of the Crips, he’d often freestyle with them about gang life to pass the time. After winning an open-mic contest judged by Kurtis Blow, he decided to treat hip-hop as his latest hustle and release his own music. “Planet Rock” had pioneered electro hip-hop in 1982; the next year, Ice-T dropped “Cold Wind Madness” in the same subgenre. “Body Rock” and “Reckless” followed, but he didn’t find his niche until “6 in the Mornin’,” under the influence of a hardcore rap single by Schoolly D.

Philly rapper Schoolly D’s discography includes 10 albums, but he first made his mark in 1985 with “Gucci Time” and the superior classic, “P.S.K. (What Does It Mean)?” For the record, “it” meant Parkside Killers, a West Philadelphia gang 23-year-old Jesse Weaver Jr. was intimately familiar with. Rarely had rap radio DJs needed to cut verses short because of profanity, violence or lewd content, but the slamming snare, booming bass and apocalyptic-sounding scratches made the song a must-play. Ice-T borrowed Schoolly’s cadence for “6 in the Mornin’,” and gangsta rap got some bullets in its chamber.

Tracy Marrow, aka Ice-T, had been a soldier and a jewel thief by the time he decided to put his rhymes on wax. As an affiliate of the Crips, he’d often freestyle with them about gang life to pass the time. After winning an open-mic contest judged by Kurtis Blow, he decided to treat hip-hop as his latest hustle and release his own music. “Planet Rock” had pioneered electro hip-hop in 1982; the next year, Ice-T dropped “Cold Wind Madness” in the same subgenre. “Body Rock” and “Reckless” followed, but he didn’t find his niche until “6 in the Mornin’,” under the influence of a hardcore rap single by Schoolly D.

Philly rapper Schoolly D’s discography includes 10 albums, but he first made his mark in 1985 with “Gucci Time” and the superior classic, “P.S.K. (What Does It Mean)?” For the record, “it” meant Parkside Killers, a West Philadelphia gang 23-year-old Jesse Weaver Jr. was intimately familiar with. Rarely had rap radio DJs needed to cut verses short because of profanity, violence or lewd content, but the slamming snare, booming bass and apocalyptic-sounding scratches made the song a must-play. Ice-T borrowed Schoolly’s cadence for “6 in the Mornin’,” and gangsta rap got some bullets in its chamber.

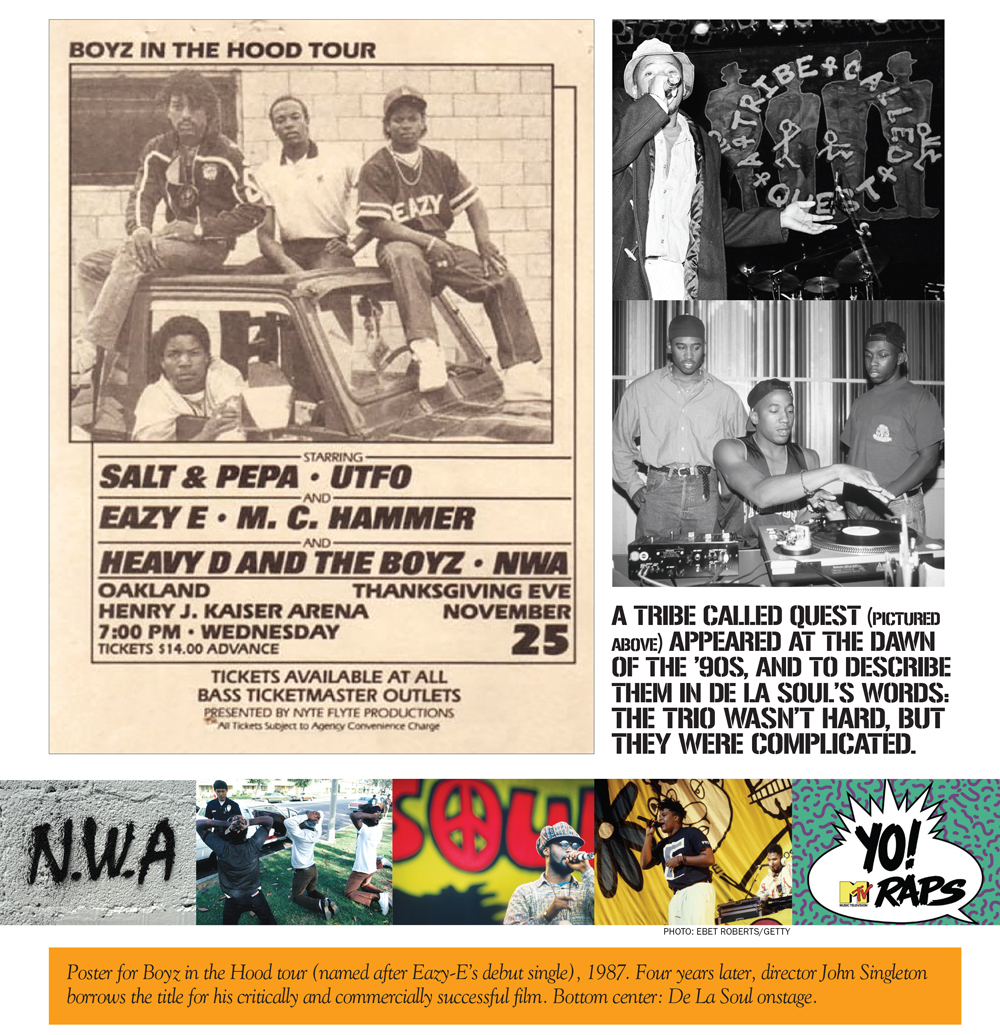

A year later, the same matter-of-fact flow suffused “Boyz-n-the-Hood,” written by an 18-year-old South Central L.A. native named O’Shea Jackson and performed by a charismatic drug dealer who called himself Eazy-E. World Class Wreckin’ Cru had decided to level up from the nightclub scene and the electro-funk of their 1985 World Class album. Andre “Dr. Dre” Young and Eric “Eazy-E” Wright hatched the idea to bring all the nihilism and ghetto reality of Compton to hip-hop music. Dre had met O’Shea “Ice Cube” Jackson when Cube’s rap group performed at World Class Wreckin’ Cru parties and, with Arabian Prince, they formed N.W.A—an acronym for Niggaz Wit Attitude. (MC Ren and DJ Yella would join afterward.) And in 1987, Straight Outta Compton altered how abrasive both rap and pop music could become—and exploded commercially.

A year later, the same matter-of-fact flow suffused “Boyz-n-the-Hood,” written by an 18-year-old South Central L.A. native named O’Shea Jackson and performed by a charismatic drug dealer who called himself Eazy-E. World Class Wreckin’ Cru had decided to level up from the nightclub scene and the electro-funk of their 1985 World Class album. Andre “Dr. Dre” Young and Eric “Eazy-E” Wright hatched the idea to bring all the nihilism and ghetto reality of Compton to hip-hop music. Dre had met O’Shea “Ice Cube” Jackson when Cube’s rap group performed at World Class Wreckin’ Cru parties and, with Arabian Prince, they formed N.W.A—an acronym for Niggaz Wit Attitude. (MC Ren and DJ Yella would join afterward.) And in 1987, Straight Outta Compton altered how abrasive both rap and pop music could become—and exploded commercially.

Controversy ensued. Eazy-E went into business with veteran tour manager Jerry Heller to form Ruthless Records for the release of an N.W.A and the Posse compilation, an Eazy-Duz-It solo album, and Straight Outta Compton. But Heller and N.W.A soon caught hell for N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police,” with a letter from the FBI warning the group never to perform the song live.

A similar storm would gather around Ice-T in 1992, for the release of his thrash band Body Count’s song, “Cop Killer.” In both cases, the attention merely served to boost the careers of both acts. And when film surfaced of the LAPD beating motorist Rodney King within an inch of his life—sparking riots when courts acquitted the officers—news pundits scoured the lyrics of gangsta rappers for insight into the African-American point of view toward L.A. law enforcement.

MTV launched Yo! MTV Raps in August 1988, bringing hip-hop into the suburban living rooms of kids who loved Guns N’ Roses and Anthrax as much as Public Enemy. Those teenagers’ peep-show view into caricatured gangster life sold a lot of records for Ice-T, N.W.A, Cypress Hill, Oakland’s Too Short, Houston’s Geto Boys and many others.

Then came the black hippies.

Controversy ensued. Eazy-E went into business with veteran tour manager Jerry Heller to form Ruthless Records for the release of an N.W.A and the Posse compilation, an Eazy-Duz-It solo album, and Straight Outta Compton. But Heller and N.W.A soon caught hell for N.W.A’s “Fuck tha Police,” with a letter from the FBI warning the group never to perform the song live.

A similar storm would gather around Ice-T in 1992, for the release of his thrash band Body Count’s song, “Cop Killer.” In both cases, the attention merely served to boost the careers of both acts. And when film surfaced of the LAPD beating motorist Rodney King within an inch of his life—sparking riots when courts acquitted the officers—news pundits scoured the lyrics of gangsta rappers for insight into the African-American point of view toward L.A. law enforcement.

MTV launched Yo! MTV Raps in August 1988, bringing hip-hop into the suburban living rooms of kids who loved Guns N’ Roses and Anthrax as much as Public Enemy. Those teenagers’ peep-show view into caricatured gangster life sold a lot of records for Ice-T, N.W.A, Cypress Hill, Oakland’s Too Short, Houston’s Geto Boys and many others.

Then came the black hippies.

New York City’s Jungle Brothers arrived first in ’88, with khaki safari outfits straight out of Banana Republic and rhyming over funky samples of Sly Stone and James Brown. The second group from the J.B.’s loosely knit Native Tongues hip-hop colony was De La Soul. Rappers Pos, Dave and DJ Maseo dropped 3 Feet High and Rising in 1989, with a yellow Day-Glo cover decorated with flowers, twice as many tracks as the average rap record, and nerdy skits as song segues. Musically they were all over the map, sampling everything from P-Funk to Johnny Cash to Schoolhouse Rock, and creating their own nerdy, playful mythology over ear-candy breakbeats (a tip of the hat here to madly eclectic producer Prince Paul). They sculpted their afro fades into layered, asymmetrical works of art. On their biggest hit single, “Me Myself and I,” the trio set the record straight early on that they weren’t hippies, even while wearing daisy-printed shirts and peace sign necklaces. But the whole concept that black bohemians could even operate within hypermasculine hip-hop didn’t exist until them. By their second album, the restlessly creative troupe was already prepared to bust its own myth: they titled it De La Soul Is Dead.

A Tribe Called Quest (Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, DJ Ali Shaheed Muhammad) appeared at the dawn of the ’90s, and to describe them in De La Soul’s words: the trio wasn’t hard, but they were complicated. That is to say, they never seemed dangerous; they seemed like me, and a million rap fans just like me. I imagined that if any MC loved, say, satirical newspaper comic strips like Calvin & Hobbes or Bloom County, Q-Tip would. The mixes on the Maxell cassettes I listened to on Bronx bus routes blended rappers like Just-Ice with my parents’ older stuff, music I imagined Q-Tip knew too. Producing People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, Q-Tip mined from the ’70s with Lou Reed, Roy Ayers, Jimi Hendrix, Weather Report and other artists that people our age weren’t really supposed to know. Tribe presented themselves in patterned dashikis with swinging leather medallions of the African continent. Phife and Q-Tip didn’t pretend to be murderous; they lusted after girls on “Bonita Applebum” instead. Like De La Soul, peace and love found its way into their material without sounding uncool.

But as the ’90s kicked off, New York City’s hold on hip-hop culture had loosened considerably. The appeal of Public Enemy’s politicized approach waned when their crack production team, The Bomb Squad, disbanded. That crew produced Ice Cube’s pivotal debut album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, when the heart of N.W.A decided to go solo in 1990. But as 70% of rap record buyers became white, pushing the genre’s albums to the top of the Billboard pop chart and into multiplatinum sales margins on a regular basis, conscious East Coast rap groups like Brand Nubian slowly fell from grace.

New York City’s Jungle Brothers arrived first in ’88, with khaki safari outfits straight out of Banana Republic and rhyming over funky samples of Sly Stone and James Brown. The second group from the J.B.’s loosely knit Native Tongues hip-hop colony was De La Soul. Rappers Pos, Dave and DJ Maseo dropped 3 Feet High and Rising in 1989, with a yellow Day-Glo cover decorated with flowers, twice as many tracks as the average rap record, and nerdy skits as song segues. Musically they were all over the map, sampling everything from P-Funk to Johnny Cash to Schoolhouse Rock, and creating their own nerdy, playful mythology over ear-candy breakbeats (a tip of the hat here to madly eclectic producer Prince Paul). They sculpted their afro fades into layered, asymmetrical works of art. On their biggest hit single, “Me Myself and I,” the trio set the record straight early on that they weren’t hippies, even while wearing daisy-printed shirts and peace sign necklaces. But the whole concept that black bohemians could even operate within hypermasculine hip-hop didn’t exist until them. By their second album, the restlessly creative troupe was already prepared to bust its own myth: they titled it De La Soul Is Dead.

A Tribe Called Quest (Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, DJ Ali Shaheed Muhammad) appeared at the dawn of the ’90s, and to describe them in De La Soul’s words: the trio wasn’t hard, but they were complicated. That is to say, they never seemed dangerous; they seemed like me, and a million rap fans just like me. I imagined that if any MC loved, say, satirical newspaper comic strips like Calvin & Hobbes or Bloom County, Q-Tip would. The mixes on the Maxell cassettes I listened to on Bronx bus routes blended rappers like Just-Ice with my parents’ older stuff, music I imagined Q-Tip knew too. Producing People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm, Q-Tip mined from the ’70s with Lou Reed, Roy Ayers, Jimi Hendrix, Weather Report and other artists that people our age weren’t really supposed to know. Tribe presented themselves in patterned dashikis with swinging leather medallions of the African continent. Phife and Q-Tip didn’t pretend to be murderous; they lusted after girls on “Bonita Applebum” instead. Like De La Soul, peace and love found its way into their material without sounding uncool.

But as the ’90s kicked off, New York City’s hold on hip-hop culture had loosened considerably. The appeal of Public Enemy’s politicized approach waned when their crack production team, The Bomb Squad, disbanded. That crew produced Ice Cube’s pivotal debut album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, when the heart of N.W.A decided to go solo in 1990. But as 70% of rap record buyers became white, pushing the genre’s albums to the top of the Billboard pop chart and into multiplatinum sales margins on a regular basis, conscious East Coast rap groups like Brand Nubian slowly fell from grace.

Coming off as the Elvis of hip-hop—commercially, at least—Miami native Vanilla Ice sold over 7 million copies of his 1990 debut album, To the Extreme (SBK). That same year, Oakland’s pop-targeted dance machine MC Hammer went even more commercial, racking up rap’s first Grammy nomination for Album of the Year with the 10-million selling Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ’Em. Still, rap’s future largely fell into the lap of gangsta rap.

A Tale of Two Coasts

Ice Cube cut his Jheri curls, joined the Nation of Islam and went solo behind a beef over being taken advantage of financially on Straight Outta Compton. Years later, Dr. Dre took flight for the same reason. His first project without Eazy-E and company turned rap around 180 degrees.

The Chronic, released in 1992, played like a Quincy Jones album, in the sense that it featured a coterie of talented artists apart from the man whose name graced the cover. Snoop Doggy Dogg—a lanky, smooth-voiced, perpetually high MC from Long Beach—broke out as The Chronic’s superstar, a rep he cemented on 1993’s Doggystyle and has lived up to ever since. The album combined P-Funk sonics (recast as G-Funk) with gangsta tropes all the way to the bank. Once The Chronic (named after a potent strain of weed) normalized marijuana use for a generation, selling quadruple platinum along the way, California became the undisputed commercial center of rap music.

NYC rappers, used to the city’s decade-long centrality, felt out of sorts. Longevity wasn’t much of a concept in rap music yet. Big Daddy Kane and Public Enemy—hot just five years earlier—weren’t releasing music that represented the zeitgeist anymore. That fell to new stars like Tupac Amaru Shakur.

Coming off as the Elvis of hip-hop—commercially, at least—Miami native Vanilla Ice sold over 7 million copies of his 1990 debut album, To the Extreme (SBK). That same year, Oakland’s pop-targeted dance machine MC Hammer went even more commercial, racking up rap’s first Grammy nomination for Album of the Year with the 10-million selling Please Hammer, Don’t Hurt ’Em. Still, rap’s future largely fell into the lap of gangsta rap.

A Tale of Two Coasts

Ice Cube cut his Jheri curls, joined the Nation of Islam and went solo behind a beef over being taken advantage of financially on Straight Outta Compton. Years later, Dr. Dre took flight for the same reason. His first project without Eazy-E and company turned rap around 180 degrees.

The Chronic, released in 1992, played like a Quincy Jones album, in the sense that it featured a coterie of talented artists apart from the man whose name graced the cover. Snoop Doggy Dogg—a lanky, smooth-voiced, perpetually high MC from Long Beach—broke out as The Chronic’s superstar, a rep he cemented on 1993’s Doggystyle and has lived up to ever since. The album combined P-Funk sonics (recast as G-Funk) with gangsta tropes all the way to the bank. Once The Chronic (named after a potent strain of weed) normalized marijuana use for a generation, selling quadruple platinum along the way, California became the undisputed commercial center of rap music.

NYC rappers, used to the city’s decade-long centrality, felt out of sorts. Longevity wasn’t much of a concept in rap music yet. Big Daddy Kane and Public Enemy—hot just five years earlier—weren’t releasing music that represented the zeitgeist anymore. That fell to new stars like Tupac Amaru Shakur.

Starting as a backup dancer with Oakland’s Digital Underground, 2Pac addressed white supremacy, black poverty, teenage pregnancy and other hot topics on 2Pacalypse Now in 1991. Charismatic and attractive, he starred in the 1992 hit film Juice and impressed many, just as Ice Cube ran away with Boyz n the Hood and Ice-T rocked New Jack City. Increasingly, 2Pac’s very existence became hip-hop’s must-watch reality show. He shot it out with cops; his interviews showed the brashness of a young Muhammad Ali.

The intricate lyricism of Rakim wasn’t quite hip-hop’s yardstick for dopeness anymore. But Nasir bin Olu Dara Jones still excited every true rap fan from Brooklyn to Compton with Illmatic. Nas emerged from the same Queensbridge housing projects that had yielded pioneer producer Marley Marl and his protégé, Roxanne Shanté. After forming a relationship with rapper-producer Large Professor of Main Source, Nas appeared on that group’s “Live at the Barbeque” the same year 2Pac debuted. When Illmatic finally dropped two years later, full of Nas’ dense, intricate rhyme flows, New York hip-hop fans found their new lyrical savior. But the album only sold at the gold (500k) level of most popular ’80s rap, not the new multiplatinum standard set by N.W.A, Dr. Dre and Snoop.

Starting as a backup dancer with Oakland’s Digital Underground, 2Pac addressed white supremacy, black poverty, teenage pregnancy and other hot topics on 2Pacalypse Now in 1991. Charismatic and attractive, he starred in the 1992 hit film Juice and impressed many, just as Ice Cube ran away with Boyz n the Hood and Ice-T rocked New Jack City. Increasingly, 2Pac’s very existence became hip-hop’s must-watch reality show. He shot it out with cops; his interviews showed the brashness of a young Muhammad Ali.

The intricate lyricism of Rakim wasn’t quite hip-hop’s yardstick for dopeness anymore. But Nasir bin Olu Dara Jones still excited every true rap fan from Brooklyn to Compton with Illmatic. Nas emerged from the same Queensbridge housing projects that had yielded pioneer producer Marley Marl and his protégé, Roxanne Shanté. After forming a relationship with rapper-producer Large Professor of Main Source, Nas appeared on that group’s “Live at the Barbeque” the same year 2Pac debuted. When Illmatic finally dropped two years later, full of Nas’ dense, intricate rhyme flows, New York hip-hop fans found their new lyrical savior. But the album only sold at the gold (500k) level of most popular ’80s rap, not the new multiplatinum standard set by N.W.A, Dr. Dre and Snoop.

The unlikeliest borough of hip-hop’s birthplace made noise too. Staten Island’s Wu-Tang Clan, a nine-man team (or nonet, if you prefer) of MCs dropping heavy allusions to martial-arts movies and Marvel superheroes, brought a new hardcore energy to rap music. Group producer RZA (born Robert Diggs) was reborn from a false start as Prince Rakeem, corralling GZA, Method Man, Ghostface, Killah, Raekwon, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, U-God, Masta Killa, Cappadonna and Inspectah Deck into the greatest rap supergroup of all time. In 1993, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)—which eventually went triple-platinum despite never cracking the Top 40—garnered much respect for the group’s tag-team rhymes, diverse personae and grimy production—and RZA carried on as one of the most respected, in-demand producers of the 1990s.

Sean “Puffy” Combs evolved from ultra-confident intern to A&R man at Andre Harrell’s Uptown Records before launching his own Bad Boy Entertainment. After grooming hip-hop soul acts like Mary J. Blige and Jodeci, the young producer/CEO went straight for the rap jugular. Craig Mack’s “Flava in Ya Ear” and “Juicy” by Brooklyn’s Notorious B.I.G. (aka Biggie Smalls, aka Christopher Wallace) set 1994 aflame. The smooth production of “Juicy” in particular—based on a sample of Mtume’s 1983 hit “Juicy Fruit”—sounded exactly like the ear-pleasing R&B that Def Jam’s Russell Simmons hated for hip-hop a decade earlier. And yet it worked anyway. Like the debuts of Wu-Tang and Nas, Biggie’s Ready to Die dropped as an instant classic. And with his omnipresence in Bad Boy’s music videos, Biggie’s success was Puffy’s as well.

The unlikeliest borough of hip-hop’s birthplace made noise too. Staten Island’s Wu-Tang Clan, a nine-man team (or nonet, if you prefer) of MCs dropping heavy allusions to martial-arts movies and Marvel superheroes, brought a new hardcore energy to rap music. Group producer RZA (born Robert Diggs) was reborn from a false start as Prince Rakeem, corralling GZA, Method Man, Ghostface, Killah, Raekwon, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, U-God, Masta Killa, Cappadonna and Inspectah Deck into the greatest rap supergroup of all time. In 1993, Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers)—which eventually went triple-platinum despite never cracking the Top 40—garnered much respect for the group’s tag-team rhymes, diverse personae and grimy production—and RZA carried on as one of the most respected, in-demand producers of the 1990s.

Sean “Puffy” Combs evolved from ultra-confident intern to A&R man at Andre Harrell’s Uptown Records before launching his own Bad Boy Entertainment. After grooming hip-hop soul acts like Mary J. Blige and Jodeci, the young producer/CEO went straight for the rap jugular. Craig Mack’s “Flava in Ya Ear” and “Juicy” by Brooklyn’s Notorious B.I.G. (aka Biggie Smalls, aka Christopher Wallace) set 1994 aflame. The smooth production of “Juicy” in particular—based on a sample of Mtume’s 1983 hit “Juicy Fruit”—sounded exactly like the ear-pleasing R&B that Def Jam’s Russell Simmons hated for hip-hop a decade earlier. And yet it worked anyway. Like the debuts of Wu-Tang and Nas, Biggie’s Ready to Die dropped as an instant classic. And with his omnipresence in Bad Boy’s music videos, Biggie’s success was Puffy’s as well.

Shawn Carter spent the late ’80s slinging drugs outside Brooklyn’s Marcy Houses projects—near the Marcy Avenue stops for the J and Z trains—and rhyming for fun. Opportunity knocked for him to guest on “Hawaiian Sophie” (a middling 1989 single by his mentor, Jaz-O); other appearances on Jaz-O and Original Flavor songs followed. But even after touring briefly with Big Daddy Kane, the MC soon known the world over as Jay-Z didn’t fully commit to hip-hop until forming Roc-a-Fella Records with partners Damon Dash and Kareem Burke in 1995. The next year, his Reasonable Doubt debut established that Jay-Z, Biggie and Nas now held the most potent pens on the East Coast. For Jay, crossover superstardom, Grammy love and pop-cultural godhead (thanks to his power coupledom with Beyoncé) awaited, and hits like “Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem)”—a brilliant repurposing of a cut from the musical Annie— “Big Pimpin’,” “Empire State of Mind” and more roiled the charts through the dawn of the millennium and well beyond.

Soon Bad Boy Entertainment and Death Row Records sat at the center of rap’s greatest tragedy. At over 300 pounds, wearing blood-red suits suggesting L.A.’s Crips gang, Death Row CEO Marion “Suge” Knight cut an imposing figure. At the 1995 Source magazine awards show, Knight hit the stage with a barely veiled dis against Puff Daddy that sowed tension between rappers from New York and California. Seven months after releasing his Death Row debut, All Eyez on Me, Tupac Shakur was murdered in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas. Six months after the Shakur homicide, two weeks before releasing Life After Death, killers shot Biggie Smalls outside a Vibe magazine afterparty in L.A. Both murders went unsolved.

Shawn Carter spent the late ’80s slinging drugs outside Brooklyn’s Marcy Houses projects—near the Marcy Avenue stops for the J and Z trains—and rhyming for fun. Opportunity knocked for him to guest on “Hawaiian Sophie” (a middling 1989 single by his mentor, Jaz-O); other appearances on Jaz-O and Original Flavor songs followed. But even after touring briefly with Big Daddy Kane, the MC soon known the world over as Jay-Z didn’t fully commit to hip-hop until forming Roc-a-Fella Records with partners Damon Dash and Kareem Burke in 1995. The next year, his Reasonable Doubt debut established that Jay-Z, Biggie and Nas now held the most potent pens on the East Coast. For Jay, crossover superstardom, Grammy love and pop-cultural godhead (thanks to his power coupledom with Beyoncé) awaited, and hits like “Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem)”—a brilliant repurposing of a cut from the musical Annie— “Big Pimpin’,” “Empire State of Mind” and more roiled the charts through the dawn of the millennium and well beyond.

Soon Bad Boy Entertainment and Death Row Records sat at the center of rap’s greatest tragedy. At over 300 pounds, wearing blood-red suits suggesting L.A.’s Crips gang, Death Row CEO Marion “Suge” Knight cut an imposing figure. At the 1995 Source magazine awards show, Knight hit the stage with a barely veiled dis against Puff Daddy that sowed tension between rappers from New York and California. Seven months after releasing his Death Row debut, All Eyez on Me, Tupac Shakur was murdered in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas. Six months after the Shakur homicide, two weeks before releasing Life After Death, killers shot Biggie Smalls outside a Vibe magazine afterparty in L.A. Both murders went unsolved.

Miles Marshall Lewis (@MMLunlimited) is the Harlem-based author of the upcoming Promise That You Will Sing About Me: The Power and Poetry of Kendrick Lamar, and his writing has appeared in Billboard, Rolling Stone, GQ and elsewhere.

Miles Marshall Lewis (@MMLunlimited) is the Harlem-based author of the upcoming Promise That You Will Sing About Me: The Power and Poetry of Kendrick Lamar, and his writing has appeared in Billboard, Rolling Stone, GQ and elsewhere.

NOW LISTEN